Selecting the right type of insulation is far more complicated that simply looking at a product’s R-value. It’s important to understand the entire long term impact of sourcing and using a particular insulation product. This means how and where the product is made, the ingredients, the waste generated during manufacturer and during installation, what happens at the end of its useful life, the R-value as tested, the R-value at extreme temperatures, the R-value long term as it ages, the vapor permeability, the air permeability, the resistance to water, the resistance to rodents and insects, the ease or difficulty in installation, the stability, the availability, and the cost. Rather than doing a deep dive, to make things easier we’ve summarized the most common insulation board products into this quick Insulation Cheat Sheet.

AVOID

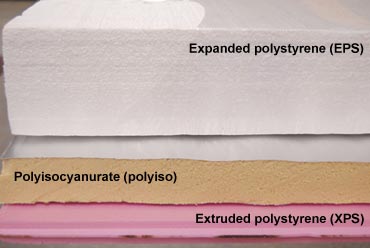

XPS FOAM

extruded polystyrene

closed cell / vapor impermeable

typical blue or pink under names “Styrofoam” and “Foamular”

R-5 / inch but loses R value as it ages. actual R-4 / inch.

suitable for below grade / underslab / comes in different densities

blowing agent (currently used in US) has very high GWP and therefore should be avoided.

High Availability / Low Initial Cost / High GWP

3 Primary Types of Foam Insulation

USE SELECTIVELY BUT BEST TO AVOID

EPS FOAM

expanded polystyrene

semi closed cell / essentially vapor impermeable unless very thin

typically white and made of tiny beads

approx R-4 / inch

suitable for below grade / underlab / comes in different densities

blowing agent has fairly low GWP.

Readily Available / Low Initial Cost / Medium Low GWP

GRAPHITE EPS FOAM

expanded polystyrene with embedded graphite particles

semi closed cell / essentially vapor impermeable unless very thin

typically white and made of tiny beads

approx R-4.5 / inch

suitable for below grade / underlab / comes in different densities

blowing agent has fairly low GWP.

Medium Availability / Low Medium Initial Cost / Medium Low GWP

POLYISOCYANURATE FOAM

typically faced with foil or felt

semi closed cell / vapor impermeable

typically yellowish / off white with silver foil facing or black felt facing

approx R-6 / inch but less R value at colder temps. actual R-5 / inch.

not suitable for below grade or underslab

blowing agent has lowest GWP of rigid foams.

most commonly use for commercial roof assemblies; used foam can sometimes be sourced.

High Availability / Low Medium Initial Cost / Low GWP

GOOD

HIGH DENSITY MINERAL WOOL

highly vapor permeable / hygrophobic (repels water)

yellow gold color

approx R-4 / inch. maintains R value at cold temperatures

now suitable for below grade or underslab

8lb per ft3 density / Roxul is most common manufacturer

low GWP but uses steel mill byproduct / energy intensive

Readily Available / Medium Cost / Low GWP

BEST

CORK

highly vapor permeable / hygrophobic (repels water)

can be used as exterior finish material if well protected

approx R-4 / inch. maintains R value at cold temperatures

not suitable for below grade or underslab

low GWP, from rapidly renewable resource,

imported from Portugal

Medium Availability / Medium to High Cost / Low GWP

WOOD FIBER BOARD

highly vapor permeable / paraffin wax provides weather resistance

doubles as WRB when used on walls

approx R-3.5 / inch. maintains R value at cold temperatures

not suitable for below grade or underslab

very low GWP but currently imported from Europe

Medium Availability / Medium to High Cost / Very Low GWP

More Cheat Sheets coming. Check back soon or subscribe for updates.